The following article was submitted by my student Tom Page. It’s a great article and offers some very interesting concepts regarding practice and learning. Great job Tom, thanks!

The chunking theory of learning is based on the concepts that:

• Performance consists of known patterns (chunks) inherent in the task you are performing

• Practice consists of acquiring the necessary patterns (chunks) that you build out of tasks already mastered.

High levels of performance are made possible by the magic of chunking. The time required to process a larger chunk is shorter than the sum of the times to process all the component chunks that comprise it. Hence, acquiring skill consists of building up increasingly larger-scale chunks, such that tasks of increasing complexity can be performed much more rapidly and fluidly than all of the underlying component skills required would imply.

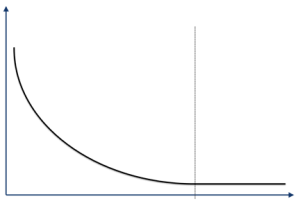

Psychologists have known the power law of practice since the 1920s. It states that the time it takes to perform a task decreases as a power-law function of the number of times the task has been performed [Snoddy, G.S., “Learning and Stability” Journal of Applied Psychology, 1926]. The basic model of practice is to acquire the skill to perform a task correctly (albeit slowly), and then to repeat that task slowly but perfectly (practice) so that the time it takes to perform it correctly improves. The power-law of practice has been shown to hold across a very wide range of human skill acquisition endeavors. A sample graph of a power-law distribution is shown below (on a linear scale).

In the above graph consider the vertical axis to represent the time it takes to perform a given task correctly (say tying your shoe). The horizontal axis represents the number of times a task has been practiced. As you can see from the curve, performance improves rapidly with practice (initially), but the marginal return on practice eventually levels off (decreasing returns). This matches our experience of watching a 5-year old tie her shoes; it takes a long time. But by the time she is 12, she can tie it about as fast as she ever will, achieving only minor improvements from then on.

The Learning Curve on Guitar

This curve also matches what most of us have experienced with respect to acquiring skill on the guitar. Improvement at first is rapid and gratifying. However, as we progress towards intermediate levels of ability, each new increment of improvement takes increasingly more input of practice. This decreasing return on practice investment can be discouraging, even causing some people to jump to other areas of skill acquisition (such as taking up golf), where they are at an earlier (and therefore more gratifying) spot on the improvement curve. However, as their skills eventually plateau there as well, they are tempted to jump to yet another arena (“maybe I’d have more fun learning to paint”). Thus, the average person either reaches his level of frustration or his level of sufficient satisfaction, and is therefore not sufficiently motivated to continue putting in the increasing additional practice input required to move further out the performance curve.

The vertical line shown past midpoint on the X-axis represents the edge of the proverbial goal of “world-class” or “virtuoso” performance. It has been proposed that to achieve world-class ability in any significant skill endeavor requires 10,000 hours of intense, focused practice. This idea seems to apply well to skills varying widely from music, to athletic performance, to chess. The message behind the 10,000 hours theory is that experts do not possess some innate talent that the rest of us lack, but rather they are extreme outliers on this power-law of practice curve. They managed to, firstly, have the quality of instruction to teach them how to perform a task correctly, and secondly, have the opportunity and drive to put in enough practice that they can perform that task correctly in a fast, effortless, and reliable way. Malcolm Gladwell’s popular book Outliers: The Story of Success is a very readable presentation of the 10,000-hours hypothesis.

How Power-Law Practice and Chunking Work Together

One model that explains the power-law of practice is the chunking theory of expertise. Various researchers have shown that experts do not have any inherently superior cognitive abilities over the rest of us. For example, chess masters who can reconstruct entire games from memory, or bridge masters with total recall of hands they played days before, do not possess measurably better memories than normal. However, studies in which the experts are requested to think aloud while completing representative tasks in their domains have revealed that experts encode information in larger “chunk sizes” than do less trained people. Experts do not simply know more; rather, they encode what they know in a way that makes domain- relevant information rapidly and reliably retrievable. A famous study in this area showed that expert chess players did no better than the average person at remembering the configuration of chess pieces when they were placed incorrectly on the board. But when shown a position from an actual game, they could reliably reconstruct the configuration from memory at far superior levels of success compared to non-chess experts.

For another example of increasing chunk size, consider the way an expert football quarterback scans a defense in the seconds before the snap. An inexperienced person sees 11 opponents in various places on the field, and in various stances, and has to reason through what each might do.

But a professional quarterback has seen all of the standard defensive configurations thousands of times. He is able to cut through all of the irrelevant detail and diagnose, for example, that the defense is in cover-two and thus he should audible to a quick underneath pass to a tight-end. Through practice repetitions, the expert quarterback has encoded, in appropriately large chunks, the information he needs to pattern match the defense immediately, and then he retrieves from memory the correct counter action.The Answer to a Paradox

The chunking theory of skill acquisition consists of recognizing the patterns that make up a task to be accomplished, and then practicing to build up the ability to perform those patterns, based on patterns already mastered. This is the answer to a basic paradox, “How can you acquire the ability to do something new by repetition of something which is not that thing you want to be able to do?” For example, if I can’t play a difficult passage, simply trying over and over is unlikely to make me able to play it. Rather, we have to take advantage simultaneously of the laws of increasing chunk size and the power-law of practice. First ,we have to build the new skill that we cannot yet do, out of more primitive chunks that we can do. (A corollary of this is that the definition of something that is too hard for us at our present level of development is that we have not yet mastered its component skills.) Once we have recognized what are the component chunks that must be sequenced to carry out the new task, then we can begin to sequence them very slowly. Through applying repetition, we can link those component chunks into a higher-level chunk. For example, a series of independent finger motions such as P A M I (four chunks) can be practiced until they become a single gesture (one higher granularity chunk) which can then be called upon to produce a tremolo pattern (an even higher-level chunk).

The Myelin Connection

Recent advances in neuro-physiology appear to explain chunking and the power-law of practice. When we perform a task, the neurological circuit in our brain that encodes that task gets reinforced with an insulating layer of myelin. The production of the myelin is called myelination. The effect of myelination on a neural circuit is to increase the speed of propagation of signals along the fiber and to provide a path for regeneration of the fiber if it is damaged. The more a neurological circuit is fired, the more its myelin is reinforced, and hence the faster it can fire, and the longer it will last. Further, circuits can be made of other, more primitive, circuits. A good book explaining this phenomenon is The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How.” by Daniel Coyle. For a guitar example, the circuit to play a free stroke with the P finger can call on the circuit that flexes the knuckle of P. Then the circuit which plays tremolo can call on the circuit that plays P, followed by the circuit that plays A, followed by the circuits for M and I. By practicing tremolo slowly, the circuit for correctly sequencing P A M and I is further myelinated, thus improving its speed and reliability. Hence, a larger tremolo chunk is built out of already-mastered chunks, and taken along the power-law of practice curve by myelination through repetition.

Fluency

Most of us have achieved expert-level performance at talking. When we have a thought to convey, we don’t have to think about what position to hold our tongue in to produce the first sound, or how much to tighten our larynx. We hardly even think about what words to say. Rather, we think in concepts and the sentences spill out, full of their meaning. This is the level of fluency of guitar playing we should aspire to. The beginning guitarist plays notes. The advancing guitarist links those notes together into lines and phrases. We move beyond where to put our fingers, and how hard to pluck, instead conceiving of whole musical phrases which our body just knows how to produce as easily as uttering a spoken sentence. Increasing the chunk size from motions of fingers, to notes, to chords, scales and arpeggios and finally to phrases and sections of pieces is what happens over the course of the 10,000 hours of focused practice. Eventually, the real skill that is practiced is the translation from a musical image that we conceive of in our brains to the production of a good approximation of that musical image, as fluidly as we speak in our native tongues.

1. Power law functions produce linear plots on log-log scale graphs.

Great article, thanks Tom and Scott.

BJ: So an efficient method of learning guitar consists

of working on a _complete_ hierarchy of chunks from

small to large. It is inefficient when chunks are missing

and are learned in a happenstance accidental manner,

and more efficient when attention is paid to them (in

particularly overlooked small chunks). And the goal is

to “myelinate” the small chunks well enough so that

they become “second nature” or automatic when

working on the larger chunks.

BJ: What about the curve? Aren’t people going to lack

patience to “master” the small chunks before going on

to larger? And isn’t there a point where mere use in

the slightly larger chunks will bring to the person the

mastery. If so, how far down the curve of mastery does

one need to go, and how does one know that he has

reached that point?

BJ: And what about the common experience of “two

steps forward and one back,” where progress is uneven

and plateaus. How does that fit into the picture?

Great questions. My thoughts are below.

BJ: So an efficient method of learning guitar consists

of working on a _complete_ hierarchy of chunks from

small to large. It is inefficient when chunks are missing

and are learned in a happenstance accidental manner,

and more efficient when attention is paid to them (in

particularly overlooked small chunks). And the goal is

to “myelinate” the small chunks well enough so that

they become “second nature” or automatic when

working on the larger chunks.

Tom: That sums it up nicely, Bob. And this is where a good teacher and a well thought out pedagogy is invaluable. The learner is seldom wise enough to recognize the base skills inherent in a complex activity. So it is the teacher’s job to guide the student through skill acquisition in a systematic manner. And this is also the role of etudes; they focus on specific skills that are preparatory for more advanced repertoire.

BJ: What about the curve? Aren’t people going to lack

patience to “master” the small chunks before going on

to larger? And isn’t there a point where mere use in

the slightly larger chunks will bring to the person the

mastery. If so, how far down the curve of mastery does

one need to go, and how does one know that he has

reached that point?

Tom: “Aren’t people going to lack patience to “master” the small chunks before going onto larger?” I think that is one of the most common problems developing guitarists have and certainly one of which I am often guilty. I want to play those pieces I hear my guitar heros play, and at the tempos they play them, rather than build up my skills playing etudes that are intentionally written to feature those more basic chunks, and at tempos where I can reinforce perfect circuits.

“And isn’t there a point where mere use in the slightly larger chunks will bring to the person the mastery.” Perhaps, but is probably not the most efficient approach.

“If so, how far down the curve of mastery does one need to go, and how does one know that he has reached that point?” That is highly individualistic. Some people may reach a point where they say, “I’m happy with my technical development; now I’m going to just have fun playing guitar.” However, I suspect that more commonly, for the personality type that gravitates to the classical guitar, the experience is that with each new mountain you succeed in climbing it only allows you to see the next, higher, mountain range beyond; never satisfied; always striving. If some magical point on the curve exists, it is more from the point of view of the rest of the world; they judge that a player has reached a virtuoso level. The player himself always knows there is more to be done. I suspect even John Williams is not completely satisfied.

BJ: And what about the common experience of “two

steps forward and one back,” where progress is uneven

and plateaus. How does that fit into the picture?

Tom:Human performance does deteriorate. Constant maintenance is required. The more completely myelinated a circuit is, the more robust it will be against deterioration, but it still deteriorates. I suspect our most common experience with “two steps forward, one step back” is with our most recently acquired skills, which will of course be our least myelinated. I’ll have to think some more about plateaus. I know they happen, and I know we can often blow past them by changing up what we are doing, but I haven’t thought through how that fits with the rest of this stuff.

Tom

BJ: Thanks, Tom. It occurred to me in your great response

that maybe the plateaus are due to hidden chunks that

have not been missed and that continued effort finally

overcomes the missing hidden small chunk. Then when it

comes that is what accounts for the surge forward.

BJ: I agree that beginners have no idea of foundational

chunks in guitar technique. That is where Scott’s material

is so helpful in identifying many of these. But I suspect

that there a nuts and bolts chunks that we all overlook.

BJ: Yes, I meant hidden small chunks that _have_ been missed,

not chunks that _have not_ been missed.

Bob,

You may be right about a plateau being a place where we are missing some foundational chunk to move forward. I am most familiar with plateaus in running and weight lifting. In those sports we often break through a new barrier and end the plateau by totally changing up what we are doing; e.g. if you have been doing a weight lifting routine with low repetitions of heavy weights, but have stopped progressing, totally change it up and do lots of reps of lighter weights. I guess that could mean that after a while we have achieved most of the benefit out of what we are doing, so doing something different hops us back onto that power law of practice improvement curve.

Tom

Tom,

I enjoyed reading your article. The Talent Code is a great book and an easy read and very accessible. Gladwell’s Outliers is a nice companion to it, focussing more on the sociological aspect of success and “talent.”

Your and Bob’s comments about plateaus are interesting. As mentioned, in sports, serious athletes use periodization in order to avoid both plateaus and injury. Might be interesting to apply the same training concept to CG.

The graph above makes me think of “marginal thinking,” which is studied a lot in economics. I use the general idea of the “law of diminishing returns.” The closer one gets to excellence, the harder and harder it becomes to make progress. Such is life.

With the many hobbies I’ve had and things I’ve done, I’ve often found that I reach a point where I have to change something in order to improve, and it’s often just doing what I am doing but doing it better, in a more focussed and efficient way rather than just doing the same thing for a longer period of time. A lot of people in this world work very hard, but you have to work smart too. I found that with guitar I suddenly would look at what I was playing and then I’d realize that it was really hard for me to play it 6 months ago and yet now it’s easy. Making progress can sneak up on you.

Lastly, motivation can’t be overlooked. Coyle uses the term “ignition.” There needs to be a balance between “chunking” and playing complete pieces. People need to keep their motivation up and most people aren’t going to be motivated if they are spending most of their time playing studies and fragments/chunks. So I would think there needs to be some balance there.

Anyway, great article!

Scott H

First off — thanks everyone for your contribution, fantastic responses to a wonderful article by Tom.

Tom states: “The basic model of practice is to acquire the skill to perform a task correctly [albeit slowly], and then to repeat that task slowly but perfectly (practice) so that the time it takes to perform it correctly improves.” (regarding the Power of Law).

I have been, over the past two years, getting ‘up to speed’ on going slow. I do this in my technique as well as repertoire work. I divide guitar playing skills into Primary and Secondary Skills. Primary Skills are required to play anything on the guitar and focus on positioning and movement forms. They must be in place at all times to move forward with our study. (This is my Phase I: Primary Skills Development which I’ll be releasing March 1st, 2012)

Secondary Skills are those skills which add to our guitar playing experience either by making the guitar and/or the music sound better or easier to play. Left hand thumb placement, vibrato, finger independence (voicing), etc. The Secondary Skills are often best applied to our technical practice first (in scales and arpeggios) and later, when ‘learned,’ applied to repertoire. Secondary Skills are those skills that once acquired must be practiced on a systematic, or regular, basis. If not, they will go away. (Primary Skills are repeated each time we play the guitar so they should always be present.)

Then I add something I call Practice Directives. Practice Directives are applied mostly to repertoire and they cover Primary and Secondary Skill sets as well as some upper end directives. Counting Measures, (phrasing), Balance, Legato, Metric Accents, Backward Sectionals, and the others are best applied to repertoire. They give the player a deeper understanding of the skills required for performance and focus on three main areas: technique; memory; musicianship.

ALL of these directives should be applied with singleness of purpose which is aided by SLOW practice. I add a Practice Directive to a piece for two weeks of practice. I focus on nothing but this directive for two weeks. I play the piece through ONCE each day I’m assigned to practice the piece. The frequency is dependent upon my level of proficiency with the piece. Then, whether I feel that I’ve accomplished this task or not I move on.

I’ve joked about this but I’m really getting intrigued with the idea of giving ‘merit badges’ for the Skill Sets. Tom joked about putting stickers on our guitars like football players do on their helmets. We could make a sticker for ‘Vibrato’ or ‘Left Hand Thumb Placement,’ meaning the player has acquired that skill as demonstrated in the performance of a piece with that skill in place.

Thanks,

Scott

Scott,

Thanks for your kind words and added thoughts.

Scott writes: “I’ve often found that I reach a point where I have to change something in order to improve, and it’s often just doing what I am doing but doing it better, in a more focussed and efficient way rather than just doing the same thing for a longer period of time.”

This is a really key point. When we have a passage we can’t yet play, it takes a fair amount of experience to analyze why we can’t play it easily. If we can play it perfectly at some tempo (even if that is ultra slow), then often we just need to let slow practice and repetition takes us along that power law of practice curve. But other times, there is something fundamental about what we are doing that is never going to work at tempo. Then, as you say, we need to figure out what that thing is and change it.

Tom

Toms article is inspirational. Lee Ryan’s book The natural classical guitar was a real turning point for me but it sounds like your teaching techniques are picking up where he left off. I would like your take on a theory of mine that hasn’t failed me yet: put more on your plate than you think you can handle don’t worry about finishing anything just go as far as you can then move to the next peice at some point when you come back to it you’ll take it further than you had previously. The only thing i do consistently everyday is segovia’s scales each one is played once.

I agree Jonathan, great article by Tom. And thanks for the compliment. I don’t know Lee Ryan’s book well but I’ve heard great things about it so thanks very much.

As to your comment, I’m not exactly sure what you mean – is it repertoire or skills that your talking about. I tend to want to manage my practice in a very organized way and in perfect world this works very well. There are times of course when we need to manage more than what comes natural and certainly a kind of learning will take place but I’m not sure I’d consider this a good long term plan. Let me know what you think!

Scott